CyberSanta

By: Hilbert

A note from the editor: My goal for these writeups is to go over the cryptography a little deeper than “This is the name of the attack, paste values into this googled script, get flag”. I want to explain what is actually going on. This however will require the use of some math. I’m going to assume you don’t absolutely hate math or you wouldn’t even be reading this, but I know that everyone has a different and varied relationship with math, and that for the inexperienced seeing a bunch of “fancy” symbols can be either intimidating or cause your eyes to glaze over (or both!). If math isn’t your strong suit, i like to think I’m up to the task of explaining things well enough that you’ll still gain some understanding and find value for your reading time and the math will always be here ready to offer a helping hand should you choose to journey farther with cryptography.

Also, since this CTF was aimed at beginners, at the end of each challenge I’ll go over how I learned the skills necessary to solve the challenge, or how one might have gone about figuring out how to solve it if it was new to them.

Jump to:

Day One (Common Mistake)

Day Two (XMAS Spirit)

Day Three (Meet Me Halfway)

Day Four (Missing Reindeer)

Day Five (Warehouse Maintenance)

Day One

Common Mistake

Clffs: Use common modulus attack to recover plaintext

The Challenge

Looking at the file we are given, we see two pieces of data

{'n': '0xa96e6f96f6aedd5f9f6a169229f11b6fab589bf6361c5268f8217b7fad96708cfbee7857573ac606d7569b44b02afcfcfdd93c21838af933366de22a6116a2a3dee1c0015457c4935991d97014804d3d3e0d2be03ad42f675f20f41ea2afbb70c0e2a79b49789131c2f28fe8214b4506db353a9a8093dc7779ec847c2bea690e653d388e2faff459e24738cd3659d9ede795e0d1f8821fd5b49224cb47ae66f9ae3c58fa66db5ea9f73d7b741939048a242e91224f98daf0641e8a8ff19b58fb8c49b1a5abb059f44249dfd611515115a144cc7c2ca29357af46a9dc1800ae9330778ff1b7a8e45321147453cf17ef3a2111ad33bfeba2b62a047fa6a7af0eef', 'e': '0x10001', 'ct': '0x55cfe232610aa54dffcfb346117f0a38c77a33a2c67addf7a0368c93ec5c3e1baec9d3fe35a123960edc2cbdc238f332507b044d5dee1110f49311efc55a2efd3cf041bfb27130c2266e8dc61e5b99f275665823f584bc6139be4c153cdcf153bf4247fb3f57283a53e8733f982d790a74e99a5b10429012bc865296f0d4f408f65ee02cf41879543460ffc79e84615cc2515ce9ba20fe5992b427e0bbec6681911a9e6c6bbc3ca36c9eb8923ef333fb7e02e82c7bfb65b80710d78372a55432a1442d75cad5b562209bed4f85245f0157a09ce10718bbcef2b294dffb3f00a5a804ed7ba4fb680eea86e366e4f0b0a6d804e61a3b9d57afb92ecb147a769874'}

{'n': '0xa96e6f96f6aedd5f9f6a169229f11b6fab589bf6361c5268f8217b7fad96708cfbee7857573ac606d7569b44b02afcfcfdd93c21838af933366de22a6116a2a3dee1c0015457c4935991d97014804d3d3e0d2be03ad42f675f20f41ea2afbb70c0e2a79b49789131c2f28fe8214b4506db353a9a8093dc7779ec847c2bea690e653d388e2faff459e24738cd3659d9ede795e0d1f8821fd5b49224cb47ae66f9ae3c58fa66db5ea9f73d7b741939048a242e91224f98daf0641e8a8ff19b58fb8c49b1a5abb059f44249dfd611515115a144cc7c2ca29357af46a9dc1800ae9330778ff1b7a8e45321147453cf17ef3a2111ad33bfeba2b62a047fa6a7af0eef', 'e': '0x23', 'ct': '0x79834ce329453d3c4af06789e9dd654e43c16a85d8ba0dfa443aefe1ab4912a12a43b44f58f0b617662a459915e0c92a2429868a6b1d7aaaba500254c7eceba0a2df7144863f1889fab44122c9f355b74e3f357d17f0e693f261c0b9cefd07ca3d1b36563a8a8c985e211f9954ce07d4f75db40ce96feb6c91211a9ff9c0a21cad6c5090acf48bfd88042ad3c243850ad3afd6c33dd343c793c0fa2f98b4eabea399409c1966013a884368fc92310ebcb3be81d3702b936e7e883eeb94c2ebb0f9e5e6d3978c1f1f9c5a10e23a9d3252daac87f9bb748c961d3d361cc7dacb9da38ab8f2a1595d7a2eba5dce5abee659ad91a15b553d6e32d8118d1123859208'}

given the variable names of ‘n’ and ‘e’ we can assume this is RSA. On closer examination we can see that the n values for both messages are the same, however the e’s differ. If the ct’s (ciphertexts) are the resulting encryptions of the same message used with these two keys, then we are able to recover the message by using a common modulus attack, which would fit with the name of the challenge. So let’s give it a go. But first…

A bit about RSA

If you aren’t very familiar with RSA don’t worry for this challenge we won’t need to understand it deeply, we’ll just briefly cover the basics we need. RSA is an asymmetric cryptography scheme, Meaning the key used for encryption is different than the one for decryption. A public key can be distributed and shared and allows anyone to use it to encrypt information, after which it can only be decrypted by a specific private key. The public key needs just two pieces of information, two different numbers. An exponent $e$ and a modulus $n$. These are created in such a way that there is a specific exponent $d$ which is kept secret and used to decrypt messages (this is the private key). The method and math behind the creation of these numbers is not important here. We just need to know that encryption is done by converting a message $m$ to a number and then raising that number to the power of $e$ modulo $n$ which produces the ciphertext $c$. If you aren’t familiar with modular arithmetic, you can think of a number “modulo $n$” as taking the number and dividing it by n and only keeping the remainder. The equation for encryption is below and would be read as “m to the e is congruent to c mod n”. \[ m^e \equiv c \pmod{n} \]

Wait, those are numbers?

If you aren’t familiar with hexadecimal, it’s just another way to represent a number. It’s like how ‘Hello’ and ‘Hola’ mean the same thing even tho they look different. Numbers are often expressed in hexadecimal because they take up less space when displayed. It also makes them easy to convert to binary which is why they are common in computer science in general. Our two ‘e’s for example displayed here using python

>>> e1 = 0x10001

>>> e2 = 0x23

>>> print(f"e1 = {e1}, e2 = {e2}")

e1 = 65537, e2 = 35

Ok, so now what?

So if we assume the same message was encrypted both times with the same modulus and it was only the exponent that was changed. The resulting ct’s (changing their names to $c_1$ and $c_2$ from here on out) would then be expressed as e \[ m^{e_1}\equiv c_1 \pmod{n} \\ m^{e_2}\equiv c_2 \pmod{n} \] We know $e_1,e_2,c_1,c_2,\text{and }n$, how do we use that to get $m$?

Get out the visine!

It’s time for some math! There is a theorem that states if you have two non zero whole numbers, $a$ and $b$, then there exists an $x$ and a $y$ that are solutions to the equation

\[

ax + by = \gcd(a,b)

\]

where $\gcd(a,b)$ is the greatest common divisor (the largest number that evenly divides them both) of the numbers $a$ and $b$ . This is known as Bézout’s identity. Looking at our two exponents $e_1$, $e_2$ we can see that

\[

\gcd(e_1, e_2) = \gcd(65537, 35) = 1

\]

(check here if you don’t believe me). So combining these 2 facts we have

\[

\begin{align}

65537x + 35 &= \gcd(65537,35) \qquad \text{or,}

\\ e_1x + e_2y &= 1

\end{align}

\]

How does that help us? Well if we knew $x$ and $y$ and could somehow get ourselves into an equation where we can evaluate $m^{e_1x + e_2y}$ we would be left with the message!

\[

m^{e_1x + e_2y} = m^1 = m

\]

Enter The Laws of Exponents. We can use the following facts

\[

\begin{align}

(x^m)^n &= x^{mn} \qquad &\text{(1)}

\\ x^mx^n &= x^{m + n} \qquad &\text{(2)}

\end{align}

\]

to achieve the following

\[

\begin{align}

&(m^{e_1})^x (m^{e_2})^y

\\ &= m^{e_1x} m^{e_2y} \quad &\text{via (1)}

\\ &=m^{e_1x + e_2y} \quad &\text{via (2)}

\\ &=m &\text{via Bézout’s Identity}

\end{align}

\]

We know $m^{e_1}$ and $m^{e_2}$. As we learned earlier that’s how RSA produces the encrypted messages! So we can just substitute

\[

\begin{align}

(m^{e_1})^x (m^{e_2})^y = (c_1)^x(c_2)^y

\end{align}

\]

and we just showed the left side of that equations reduces to $m$. However we started with a congruence relation, not strict equalities, what we really have is

\[

\begin{align}

(m^{e_1})^x (m^{e_2})^y \equiv (c_1)^x(c_2)^y \pmod{n}

\\ m^{e_1x + e_2y} \equiv (c_1)^x(c_2)^y \pmod{n}

\\ m \equiv (c_1)^x(c_2)^y \pmod{n}

\end{align}

\]

so all we have to do now is find $x$ and $y$ by solving

\[

65537x + 35y = 1

\]

Enter the Extended Euclidean Algorithm. The Euclidean algorithm is a famous algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor of two integers. It does this by repeatedly dividing the divisor by the reaminder until nothing is left. The extended algorithm works its way backwards, by starting with the gcd and eventually expressing it as a linear combination of the original two numbers. We can use this to solve the above formula. Using this tool we get values of -2 and 3745 for $x$ and $y$ respectively.

Are we there yet?

Now we just plug those numbers in and let ‘er rip right? Well, not quite. We have one small issue. We need to calculate \[ c_1^{-2}c_2^{3745} \mod{n} \] What is a number raised to a negative power? From our Laws of Exponents we know that $c_1^{-2}$ is the same thing as $(c_1^{-1})^{2}$, but what is $c_1^{-1}$? You may know that a number to a negative exponent means “take its inverse” or “reciprocal” and are used to treating it like the following \[ x^{-1} = \frac{1}{x} \] However here we are working with the integers modulo $n$, which are whole numbers, not with the typical real numbers (any number you can point to on the number line). Fractions don’t exist in this world.

Enter the multiplicative inverse. The multiplicative inverse of a number is the number you need to multiply it by to get the number one. [pedantic math note: strictly speaking this is not true. It is the number you need to multiply by to get the Identity Element, but for the sake of brevity we will ignore all that]. This is why for example $7^{-1} = \frac{1}{7}$ because \[ 7 \times \frac{1}{7} = 1 \] So what we need then is the number that fits in \[ c_1 \times ? \equiv 1 \pmod{n} \] We can actually use our new friend the Extended Euclidean Algorithm to find this. We’ve seen that we can use it to solve Bézout’s identity problems, and for reasons we can ignore, we can assume that the $\gcd(c_1, n) = 1$, and so look what we have if we find the solutions for the Bézout’s Identity \[ \begin{align} &c_1x + ny = \gcd(c_1, n) \\ & c_1x + ny = 1 \\ &c_1x = -ny + 1 \\ \Rightarrow \quad &c_1x \equiv 1 \pmod{n} \end{align} \] this last step might look confusing, but because $c_1x$ equals one more than some multiple of $n$ (specifically we have negative $y$ multiples of it), we can transform the third line into the fourth, because having one more than some multiple of $n$ means we will have a remainder of one when we divide it by $n$, which is how we defined modular arithmetic earlier.

Since $n$ is a rather quite large number, we won’t plug it into the same online tool, but now that we know how to find it, we have the last piece to our puzzle and we can now write up some python code to retrieve the message by calculating \[ (c_1^{-1})^{x}c_2^{y} \mod{n} \]

CTRL-C, CTRL-V

You will need pycryptodome to run the following

# pycryptodome

from Crypto.Util.number import inverse, long_to_bytes

import json

def bezout(a, b):

""" Calculates ax + by = gcd(a,b) (Bezout's Identity) using the

Exetended Euclidean Algorithm. Ripped straight off the pseudocode

at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_Euclidean_algorithm

returns (x, y, gcd(a,b))

"""

old_r = a

r = b

old_s = 1

s = 0

old_t = 0

t = 1

while (r != 0):

q = old_r // r

tmp_r = r

r = old_r - q * tmp_r

old_r = tmp_r

tmp_s = s

s = old_s - q * tmp_s

old_s = tmp_s

tmp_t = t

t = old_t - q * tmp_t

old_t = tmp_t

return (old_s, old_t, old_r)

# Read in our file

with open('encrypted.txt') as f:

msg1 = json.loads(f.readline().replace("'", '"')) #json whines about single quotes

msg2 = json.loads(f.readline().replace("'", '"'))

# fill all the variables for our calculation, They are hex strings, so we convert to ints

n = int(msg1['n'], 16)

e_1 = int(msg1['e'], 16)

e_2 = int(msg2['e'], 16)

c_1 = int(msg1['ct'], 16)

c_2 = int(msg2['ct'], 16)

# we could use the bezout function for this but pycrytodome provides us

# with a simple way to get the inverse of a number modulo n

c_1_inv = inverse(c_1, n)

# x and y from our equation e_1x + e_2y = gcd(e_1, e_2)

(x, y, z) = bezout(e_1, e_2)

# calculating the message

m = pow(c_1_inv, -x, n) * pow(c_2, y, n) % n

# We could actually use pow(c_1, x, n) as python will automatically calculate the

# inverse (it will error if it doesnt exist) when we use a negative exponent

# and the modulus parameter, but I thought it would be helpful to explain inversion.

#m = pow(c_1, x, n) * pow(c_2, y, n) % n

# m is a decimal number we'll use pycrptodome to convert to bytes

flag = long_to_bytes(m)

print(flag.decode())

Flagged!

HTB{c0mm0n_m0d_4774ck_15_4n07h3r_cl4ss1c}

Knowing that this challenge involves the use of RSA is just a little bit of experience. N and e are the standard variable names for RSA, so if you ever see those, that’s what it will be. I learned this particular vulnerability by doing a similar challenge on HTB (It’s still active, go find it for some free points!). Seeing that the modulus was the same for two messages and googling something to the effect of “same N RSA attack”, (always put ‘attack’ in your crypto searches) will bring you to lots of information. Then I sat down and went over the math until I thought I understood it, and then did a write up on it so I could remember it better (or refer back to it everytime I ran across another Common Modulus attack).

Day Two

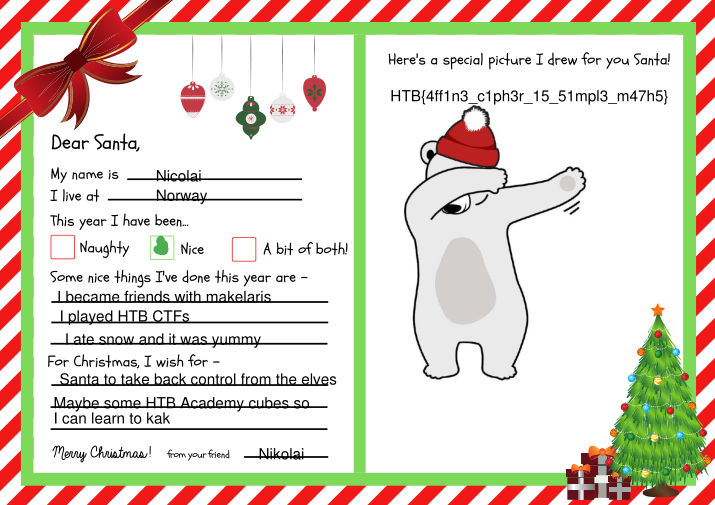

XMAS Spirit

cliffs: Use modular inversion to reverse the encryption forumula. Try all possible combinations of a and b to decrypt the first four bytes of the file until we get a valid PDF file signature , then use those values to decrypt the entire file.

update: It was pointed out to me by a friend that there is a much simpler way to solve this challenge. We have two equations and two unkowns and so can solve for $a$ and $b$ directly. I will add this method after all the stuff I wrote originally.

The Challenge

Looking at the code used to encrypt the letter

#!/usr/bin/python3

import random

from math import gcd

def encrypt(dt):

mod = 256

while True:

a = random.randint(1,mod)

if gcd(a, mod) == 1: break

b = random.randint(1,mod)

res = b''

for byte in dt:

enc = (a*byte + b) % mod

res += bytes([enc])

return res

dt = open('letter.pdf', 'rb').read()

res = encrypt(dt)

f = open('encrypted.bin', 'wb')

f.write(res)

f.close()

we see that a random $a$ from $1$ to $256$ where $gcd(a,256) = 1$ is chosen. This means that $a$ and $256$ don’t share any factors. Since $256 = 2^8$ its only factor is $2$, so $a$ is then an odd number below $256$. Next a random $b$ from $1$ to $256$ is chosen, and then the letter.pdf file is iterated over a byte at a time and each byte is transformed into a different byte via the equation

enc = (a*byte + b) % mod

This from of transformation is called an affine cipher.

Decryption = noitpyrcnE

So how do we undo this? Decryption here is encryption in reverse, where we undo the action performed at each step. To encrypt, we took a value, multiplied it by $a$ then added $b$. So to decrypt we will subtract $b$, and then divide by $a$. This is all done modulo 256 of course. And that leads us to a problem. The way modular arithmetic is defined we can’t simply divide in the way you are likely used to. One of the reasons for which is because modular arthmetic takes place over the integers, which are whole numbers. What then is 79 divided by 123?

Deja vu all over again

We went over multiplicative inversion in the last challenge, but we are going to touch on it again here. Both because it’s a super important concept and also because I’m copy and pasting from another write up I did and it’s easier this way. (This challenge is also essentially a duplicate of an active HTB crypto challenge, go get those free points!)

Multiplication is the repeated addition of a number, while division is the repeated subtaction of a number. Multiplication and division are opposite operations, they are the inverse of each other. So one way to think of division is the multiplication of a number by its inverse. What then is a numbers inverse? The inverse of a number is defined as the number which when multiplying our number by, gives 1 as the result.

So when you divide both sides of some equation like $7x = 56$ by $7$ to get $x = 8$, you are really multiplying both sides by the inverse of $7$. $(\frac{1}{7})7x = (\frac{1}{7})56$

The inverse of a number isn’t always guaranteed to exist however. In our world of modular arithmetic, for the inverse of a number to exist, it can’t share any factors with the modulus, i.e. it and the modulus have a GCD of one. This is why that check was performed in the code. Without it, it might not have been possible to reverse the encryption.

So we know the equation can be reversed and from the previous section we know how to get a numbers inverse, but we don’t know $a$ or $b$, so what do we do? We try them all of course!

Psssst, hey you, wanna buy some magic beans?

So we’ve got 128 different choices for $a$ and 256 different choices for $b$, which means we have $128 \times 256 = 32768$ possibilities. If you’ve opened the encrypted.bin file and looked at how long it is or noticed it’s size (759KB), decrypting it that many times and seeing if we have an output that makes sense would take a looong time, several days in fact. Is this why they gave this challenge to us on day 2, so we’d have time to finish? Thankfully no. We can use something called ‘magic bytes’, these are numbers used to identify or verify the content of a file. In our case we can see here that a valid PDF file should start out with with the bytes \x25\x50\x44\x46 or %PDF. So instead of decrypting the entire file, we only need to decrypt the first 4 bytes and then we’ll know if we need to bother with the rest.

Psssst, wanna know a better way? (updated solution)

Long after this challenge came out, a friend was reading this and said “why didn’t you do it this way?” and I went “uhhh…..that’s a good question!”. The crux of the problem is trying to recover the values for $a$ and $b$, if we have those then we can perform the decryption. The method I used originally and detailed above was using brute force to try all of them until we find the ones that work. But we can solve for them directly. Because of the aforementioned ‘magic bytes’ of the PDF file, we know what the very first values to be encrypted were, and we also have the encrypted output so we know what they become. We can therefore create two equations with only two unkowns, and solve it.

\[ \begin{align} &37a + b \equiv 13 \pmod{256} \\ & 80a + b \equiv 112 \pmod{256} \end{align} \]

Where 37 and 80 are the decimal values of the first two magic bytes (\x25\x50) and 13 and 112 are the first two values of the encryption. We can then use one of the many methods available for solving a system of linear equations. If we subtract the 2nd equation from the first we get

\[ 43a \equiv 99 \pmod{256} \]

We can then solve for $a$ by dividing both sides by 43, which as we detailed above is achieved by multiplying by the inverse of 43 modulo 256

\[ a \equiv 99 \cdot (43)^{-1} \equiv 99 \cdot 131 \equiv 169 \pmod{256} \]

We can then substitute the value of $a$ into one of the equations to solve for $b$

\[ \begin{align} 37 \cdot 169 + b & \equiv 13 \pmod{256} \\ \Rightarrow \quad b & \equiv 160 \pmod{256} \end{align} \]

We can then decrypt the message as we had originally intended.

As for why I didn’t originally detail this method or use it, I honestly don’t remember. I tend to think of the brute force solution first when I try and solve something, and in the case of a problem like this where the space is so small I probably never even stopped to think if there was a better way. Also I lacked the experience of doing many of these to instantly think of it as a system of equations. It’s a prime example of why I make write ups and try and share any knowledge I do acquire, because they lead me to thinking deeper about things in the effort to try and explain it, but also because it provides an opportunity for people to point out better methods or mistakes.

It’s also a good way to document where you are at certain points in your learning. If you go back to something you wrote in the past and see there are gaps in your knowledge, that is a wonderful way to see tangible growth in your journey. Being able to see that growth often eludes us because it happens so slowly we don’t notice it, and it’s easy to fall into the trap of being down on yourself for not knowing more than you do. When you can actually see progress its invigorating and inspiring.

CTRL-C, CTRL-V

# function that reverses the encryption

def decrypt(ct, a, b):

a_inv = pow(a, -1, 256)

pt = b''

for byte in ct:

# subtract b, "divide" by a

dec = ((byte - b) * a_inv) % 256

pt += bytes([dec])

return pt

# function to check all possible a,b values to find

# the one that decrypts a valid PDF file

def get_ab(header):

for a in range(1,256,2): # odd numbers

for b in range(1,256):

if decrypt(header, a, b) == b'%PDF':

return a,b

def get_ab_directly(c1, c2):

# read the binary encrypted file

with open('encrypted.bin', 'rb') as f:

ct = f.read()

# The encrypted 'magic bytes'

header = ct[:4]

# find a,b

a,b = get_ab(header)

# Decrypt the letter

pt = decrypt(ct,a,b)

# write decrypted PDF to file system

with open('letter.pdf', 'wb') as f:

f.write(pt)

Flagged!

Knowing how to undo the encryption comes from familiarity with modular arithmetic and related concepts. Often googling bits of code if you are unfamiliar or stuck can get you helpful information. Here googling “How to reverse (a*byte + b) % mod” gets you lots of hits about bytes and bit related things which we don’t want, but simply taking out that word so we lose those results and replacing it with “How to reverse (ax + b) % mod” provides the answers you would need.

Knowing about magic bytes is also a function of experience as it’s something that comes up in web challenges, frequently related to bypassing file upload restrictions. If you didn’t know this tho, think about how you could speed up decryption if you were confronted with the days long wait, you obviously wouldn’t need to decrypt the entire file to know whether it’s gibberish or not. But how much would you need to decrypt? That might get you googling things like “How to tell if a file is a PDF” or “how is text stored in a PDF?”, or even just opening up some PDFs and seeing what they look like could get you the information you need to reduce the time to something reasonable.

Day Three

Meet Me Halfway

cliffs: Use Meet In The Middle attack to reduce number of operations to something easily brute forceable and recover the keys, then decrypt message.

The Challenge

Going over the provided source code, we see that the general operation of the challenge is that we can connect to the evil elves service, where we are given the encryption of the flag. We are also able to provide our own plaintext and it’s encrypted value will be returned to us.

The two important functions are how the encryption keys are generated and then how it’s encrypted

def gen_key(option=0):

alphabet = b'0123456789abcdef'

const = b'cyb3rXm45!@#'

key = b''

for i in range(16-len(const)):

key += bytes([alphabet[randint(0,15)]])

if option:

return key + const

else:

return const + key

def encrypt(data, key1, key2):

cipher = AES.new(key1, mode=AES.MODE_ECB)

ct = cipher.encrypt(pad(data, 16))

cipher = AES.new(key2, mode=AES.MODE_ECB)

ct = cipher.encrypt(ct)

return ct.hex()

We can see that depending on a parameter the gen_key function either returns four random characters from the given alphabet concatenated with const, or the other way around, const then the four random characters.

The encryption function takes two keys, and then double encrypts the data with AES. First encrypting it with key1, and then encrypting that encryption with key2.

Via the challenge function we see that

k1 = gen_key()

k2 = gen_key(1)

each method to generate a key is used. So we have k1 which is a 16 byte key with the last four bytes unknown to us and k2, a 16 byte key where the first four bytes are unknown. The key space from which each of these bytes are chosen is a set of 16 characters, the numbers 0 through 9 and the letters a through f. This mean there are 16 possibilities for each of the 8 unknown bytes. This equates to $16^8 = 4294967296$ different possible values if we were to brute force our way to the solution as the code is written. If this number looks familiar it’s because it’s $2^{32}$ which is a number of significance in computer science. Now 4.2 billion isn’t a space so large that we couldn’t check every single possibility and get our answer. You could leave your computer running overnight and expect to awake to the answer in the morning. However there is a method that will allow us to find the answer much faster, in about a second actually.

Meet me in the middle

AES is what’s called a symmetric encryption algorithm, this means that the same key is used for both encryption and decryption. (Unlike RSA which we encountered earlier). If we look at the encryption being done here like moving forward on a map were we go from A $\xrightarrow{\text{encrypt}_1}$ B $\xrightarrow{\text{encrypt}_2}$C, to get to every C we have to try every A, and for each of those, then we try every B which as we discussed is a lot of trips. What if however we go from all the possible A $\xrightarrow{\text{encrypt}}$ B and record each one. Then since we can encrypt and decrypt with the same key (meaning we can also travel backwards) we go from all the possible C $\xrightarrow{\text{decrypt}}$ B and record each one? We could then check and see if we ended up at the same B in any of our trips going from each direction. Meaning we will have found a route like so, A $\xrightarrow{\text{encrypt}_1}$ B $\xleftarrow{\text{decrypt}_2}$ C. How does that help? Well there are $16^4$ possibilities for each key, but now since we don’t have to walk the whole path at once instead of trying $16^4 \times 16^4 = 16^8$ possibilities, we are just doing $16^4$ possibilities twice, or $16^4 + 16^4$. This is a much smaller number, in fact it’s just $2^9 = 131072$ possibilities. So we went from over 4 billion to a litle over 130 thousand. In fact it’s even a little better than that. We have to check all the ways to get to B from one direction, but we don’t need to check all the ways to get to B from the other direction. Once we find a B we’ve already been to, our search is over, so we can stop!

Following the yellow brick road

We are given the encryption of the flag, but since we don’t know what it was originally we can’t meet in the middle. We need to know the start and the end points. So how nice is it of those supposedly evil elves to provide us with exactly that by returning for us the encryption of any plaintext we give them! We’ll simply pick anything we want (our A) and then they’ll provide us with the end result (our C) and then we will look for a path to meet in the middle.

CTRL-C, CTRL-V

# pycrptodome

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

import itertools

# This is our single encrypt function, we can simply erase the second encrption

# from the one they provided us with

def encrypt(data, key):

cipher = AES.new(key, mode=AES.MODE_ECB)

ct = cipher.encrypt(pad(data, 16))

return ct

# This is our decryption function, since AES is symmetric we don't have to do

# much other than change a word (and remove the call for padding)

def decrypt(data, key):

cipher = AES.new(key, mode=AES.MODE_ECB)

pt = cipher.decrypt(data)

return pt

# From the original code, we need these to generate all the possible keys

alphabet = b'0123456789abcdef'

const = b'cyb3rXm45!@#'

# This is our plaintext, or A our starting point, we can choose anything

pt = b'hello world'

# This hex is the encryption of pt provided by those kindly elves

ct2 = bytes.fromhex('5b6e4a3e168a3d64f1e61db4cb9b7147')

# The encrypted flag

flag = bytes.fromhex('fa4d5fbab839a429105c890490d880f1bf40b087a453875bd629fcb6eda55409271812f89776c1fb506c5b06b2b111b6534a8e4d6bd4bff90c2f940063c0b34160bc919a719035de754155bddaa7f25761caa85398ada53d2610d55fa0f4a5a0')

# Dictionary where we will store the information of all our travels from A -> B

encryptions = {}

# A -> B

for p in itertools.product(alphabet, repeat=4): # gets all 65536 possibilities of 4 items taken from alphabet (with repeats, meaning we can have 'aaaa')

key = const + bytes(p) # p is a tuple of ints, so we convert to bytes

ct1 = encrypt(pt, key)

encryptions[ct1] = key

# C -> A

for p in itertools.product(alphabet, repeat=4):

key = bytes(p) + const

ct1 = decrypt(ct2, key)

if ct1 in encryptions: # We found a B we've visited

k1 = encryptions[ct1] # the key we used to go A -> B

k2 = key

break

# we have both keys now, so we can decrypt twice to get back the original flag

flag = decrypt(flag, k2)

flag = decrypt(flag, k1)

flag = unpad(flag, 16)

print(flag.decode())

Flagged!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZMv9XO4NlkHTB{h45hpump_15_50_c001_h0h0h0}

Knowing this technique exists is experience in either having seen such an attack before or from study done in algorithms, typically via one of the various coding challenge sites.

The best general approach if you are struggling is to attempt to figure out the naive method (aka brute force). In any challenge if the answer can be had if you can guess correctly, then try and figure out how you could guess every single possibility. This option is always available in cryptography, the security comes from the fact it can take in some cases trillions of years to iterate over all the possibilities, but it’s always there. If you can figure out how you could make every guess, then you can count how many guesses that is, and then calculate how long it would take. This challenge for example you could have worked to figure out it would require ~4 billion guesses, then timed how long say 100,000 guesses took and then worked out that you could get the answer after several hours. You either could have then let it run and worked on other things, or continued to work on trying to figure out a way to improve upon that time but with the peace of mind that you can get the answer worst case.

Day Four

Missing Reindeer

cliffs: Too small an exponent was used and the message never wrapped around the modulus. Taking the cube root returns the original message

The Challenge

Examining the intercepted email we see that it contains an encrypted message along with the public key that was used to encrypt it.

------=_Part_5028_7368284.1115579351471

Content-Type: application/text/plain; name*=secret.enc

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

Content-Disposition: attachment

Ci95oTkIL85VWrJLVhns1O2vyBeCd0weKp9o3dSY7hQl7CyiIB/D3HaXQ619k0+4FxkVEksPL6j3wLp8HMJAPxeA321RZexR9qwswQv2S6xQ3QFJi6sgvxkN0YnXtLKRYHQ3te1Nzo53gDnbvuR6zWV8fdlOcBoHtKXlVlsqODku2GvkTQ/06x8zOAWgQCKj78V2mkPiSSXf2/qfDp+FEalbOJlILsZMe3NdgjvohpJHN3O5hLfBPdod2v6iSeNxl7eVcpNtwjkhjzUx35SScJDzKuvAv+6DupMrVSLUfcWyvYUyd/l4v01w+8wvPH9l

------=_Part_5028_7368284.1115579351471

Content-Type: application/octet-stream; name*=pubkey.der

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

Content-Disposition: attachment

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIIBIDANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ0AMIIBCAKCAQEA5iOXKISx9NcivdXuW+uE

y4R2DC7Q/6/ZPNYDD7INeTCQO9FzHcdMlUojB1MD39cbiFzWbphb91ntF6mF9+fY

N8hXvTGhR9dNomFJKFj6X8+4kjCHjvT//P+S/CkpiTJkVK+1G7erJT/v1bNXv4Om

OfFTIEr8Vijz4CAixpSdwjyxnS/WObbVmHrDMqAd0jtDemd3u5Z/gOUi6UHl+XIW

Cu1Vbbc5ORmAZCKuGn3JsZmW/beykUFHLWgD3/QqcT21esB4/KSNGmhhQj3joS7Z

z6+4MeXWm5LXGWPQIyKMJhLqM0plLEYSH1BdG1pVEiTGn8gjnP4Qk95oCV9xUxWW

ZwIBAw==

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

------=_Part_5028_7368284.1115579351471--

DERp

From the email we see the name of the attached public key is pubkey.der, what exactly is that? From the first challenge we learned that a public key is made up of some variables, and that is what is used to encrypt a message. But just sending out a text file with some long numbers in it isn’t a very efficient or sensible way to distribute that information. So like all things, some kind of standard was created, and there are lots of acronyms and differences to get confused by, and well DER is an encoding that is a variation of the more general X.690 encoding and is the de-facto standard for encoding ASN.1 structures, which is often then further encoded in base64 and given a header and footer and called a PEM file, which stands for Privacy Enhanced Mail, which has nothing to do anymore with mail, and such pem files are given the extension .pem or .crt because it can also contain X.509 certificates, and come on, all that is way worse than any unreadable wall of math equations.

Basically whenever you see

—–BEGIN PUBLIC KEY—–

—–END PUBLIC KEY—–

and a bunch of base64 in the middle you’ve got a public key and it can be used to encrypt stuff, and we want to get the information out of it so we can get a flag and all the glory that comes with.

Open Sesame

The tool we are going to use to read these types of files is a command line tool named openssl. We can simply copy and paste everything into a file on our computer, making sure to include the header and footer like so

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIIBIDANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ0AMIIBCAKCAQEA5iOXKISx9NcivdXuW+uE

y4R2DC7Q/6/ZPNYDD7INeTCQO9FzHcdMlUojB1MD39cbiFzWbphb91ntF6mF9+fY

N8hXvTGhR9dNomFJKFj6X8+4kjCHjvT//P+S/CkpiTJkVK+1G7erJT/v1bNXv4Om

OfFTIEr8Vijz4CAixpSdwjyxnS/WObbVmHrDMqAd0jtDemd3u5Z/gOUi6UHl+XIW

Cu1Vbbc5ORmAZCKuGn3JsZmW/beykUFHLWgD3/QqcT21esB4/KSNGmhhQj3joS7Z

z6+4MeXWm5LXGWPQIyKMJhLqM0plLEYSH1BdG1pVEiTGn8gjnP4Qk95oCV9xUxWW

ZwIBAw==

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

and then we will use the asn1parse option in openssl just to find out exactly what it is we are dealing with

└─$ openssl asn1parse -in pubkey.der

0:d=0 hl=4 l= 288 cons: SEQUENCE

4:d=1 hl=2 l= 13 cons: SEQUENCE

6:d=2 hl=2 l= 9 prim: OBJECT :rsaEncryption

17:d=2 hl=2 l= 0 prim: NULL

19:d=1 hl=4 l= 269 prim: BIT STRING

Don’t worry if none of that makes sense, we only care about the part where it says ‘:rsaEncryption’. Now that we are sure we have an RSA public key, lets get the information we want out of it, the $N$ and $e$ values. We’ll use openssl again, but this time with the rsa option

└─$ openssl rsa -pubin -in pubkey.der -text -modulus -noout

RSA Public-Key: (2048 bit)

Modulus:

00:e6:23:97:28:84:b1:f4:d7:22:bd:d5:ee:5b:eb:

84:cb:84:76:0c:2e:d0:ff:af:d9:3c:d6:03:0f:b2:

0d:79:30:90:3b:d1:73:1d:c7:4c:95:4a:23:07:53:

03:df:d7:1b:88:5c:d6:6e:98:5b:f7:59:ed:17:a9:

85:f7:e7:d8:37:c8:57:bd:31:a1:47:d7:4d:a2:61:

49:28:58:fa:5f:cf:b8:92:30:87:8e:f4:ff:fc:ff:

92:fc:29:29:89:32:64:54:af:b5:1b:b7:ab:25:3f:

ef:d5:b3:57:bf:83:a6:39:f1:53:20:4a:fc:56:28:

f3:e0:20:22:c6:94:9d:c2:3c:b1:9d:2f:d6:39:b6:

d5:98:7a:c3:32:a0:1d:d2:3b:43:7a:67:77:bb:96:

7f:80:e5:22:e9:41:e5:f9:72:16:0a:ed:55:6d:b7:

39:39:19:80:64:22:ae:1a:7d:c9:b1:99:96:fd:b7:

b2:91:41:47:2d:68:03:df:f4:2a:71:3d:b5:7a:c0:

78:fc:a4:8d:1a:68:61:42:3d:e3:a1:2e:d9:cf:af:

b8:31:e5:d6:9b:92:d7:19:63:d0:23:22:8c:26:12:

ea:33:4a:65:2c:46:12:1f:50:5d:1b:5a:55:12:24:

c6:9f:c8:23:9c:fe:10:93:de:68:09:5f:71:53:15:

96:67

Exponent: 3 (0x3)

Modulus=E623972884B1F4D722BDD5EE5BEB84CB84760C2ED0FFAFD93CD6030FB20D7930903BD1731DC74C954A23075303DFD71B885CD66E985BF759ED17A985F7E7D837C857BD31A147D74DA261492858FA5FCFB89230878EF4FFFCFF92FC292989326454AFB51BB7AB253FEFD5B357BF83A639F153204AFC5628F3E02022C6949DC23CB19D2FD639B6D5987AC332A01DD23B437A6777BB967F80E522E941E5F972160AED556DB7393919806422AE1A7DC9B19996FDB7B29141472D6803DFF42A713DB57AC078FCA48D1A6861423DE3A12ED9CFAFB831E5D69B92D71963D023228C2612EA334A652C46121F505D1B5A551224C69FC8239CFE1093DE68095F7153159667

-pubin tells it to expect a public key as input

-in gives it the name of the file

-text tells it to show the bytes of the modulus and the value of the exponent

-modulus tells it to print the hex value of the moduls in that much nicer format we can copy and paste

-noout tells it not to print the contents of the file. Which I have no idea why isn’t the default, but it’s not

Now the thing to notice here is that the exponent is 3. This doesn’t necessarily mean anything, 3 is a perfectly valid value for $e$ but it does introduce some methods of attack if everything is not implemented correctly. The “standard” value for $e$ is 65537 or 0x10001 in hex. Given that this is a CTF anytime you see a value for $e$ that isn’t that, it most likely means something.

Let’s go ahead and look at the ciphertext. We’ll use python to convert it from base64 to an integer.

>>> ct = base64.b64decode(b'Ci95oTkIL85VWrJLVhns1O2vyBeCd0weKp9o3dSY7hQl7CyiIB/D3HaXQ619k0+4FxkVEksPL6j3wLp8HMJAPxeA321RZexR9qwswQv2S6xQ3QFJi6sgvxkN0YnXtLKRYHQ3te1Nzo53gDnbvuR6zWV8fdlOcBoHtKXlVlsqODku2GvkTQ/06x8zOAWgQCKj78V2mkPiSSXf2/qfDp+FEalbOJlILsZMe3NdgjvohpJHN3O5hLfBPdod2v6iSeNxl7eVcpNtwjkhjzUx35SScJDzKuvAv+6DupMrVSLUfcWyvYUyd/l4v01w+8wvPH9l')

>>> ct = int(ct.hex(), 16)

>>> ct

3778608670452741690585532070582737668282151949640402971008788675797867361769689843795603772570139166588578774047027062261466175271392436524653959718229204843915061726484932376601163405265201763831847338823471193932707736077364458453053284027613438860180982451957373644892420683829816445662870127785631688212264667656902285465215893696422157358833968897797828703078065238512429996646780856030831270941538206089269140998459840179372535825110571621961016595399813535271853291603009139930478398009395635275428350832860405110482112603276542371203486280518726687143561313790881202021

>>> len(bin(ct))

1918

>>>

b64decode() requires the input to be in bytes so we wrapped it in b’’ to make it a byte string. The output is the decoded bytes. We then converted that to a hex string and turned that into an integer. After displaying the integer value, we check and see how many bits that number is, which happens to be 1916 bites (the bin() function in python converts the number to a string of the binary representation of the number with a leading ‘0b’, so that’s why the actual value is two less than the output)

Never tell me the odds

Now given that our modulus is 2048 bits, it would be incredibly rare for our encrypted message to also not be roughly that size. If we assumed that the output of an encrypted message was random and could be any of the numbers smaller than the modulus (this isn’t actually the case, but the point will still hold), more than half of all those numbers are 2047 bits or greater, more than 75% are 2046 bits or greater, more than 87.5% are 2045 bits or greater, more than 93.75% are 2044 bits or greater….see where I’m going with this? By the time we get down to 1916 bits, we are well into the realm of “not bloody likely”.

So what does this mean?

Let’s look a couple of extreme examples. What would happen if we chose $e=1$ for our encryption exponent? Let’s say the value of our message is $123456789$, and we’ll use $N = 1234567891011$ for our modulus. The formula again for RSA encryption is $c \equiv m^e \pmod{N}$

\[ c \equiv 123456789^1 \equiv 123456789 \pmod{1234567891011} \]

This would obviously be terrible, our ciphertext and our plaintext are exactly the same, anyone would simply be able to read our original message. Let’s look at another extreme example. This time we’ll use $e=3$ with the same $N$ but let’s say our message is simply the number $5$

\[ c \equiv 5^3 \equiv 125 \pmod{1234567891011} \]

well our ciphertext differs from our plaintext so why is this bad? Well one of the reasons RSA even works as an encryption scheme is because taking nth roots modulo $N$ is really really hard. But that requires our message when raised to the power of $e$ be larger than the modulus so that when its reduced mod $N$ we lose all that information. If it doesn’t grow larger than $N$ then whatever $N$ is is irrelevant, we are just taking an nth root over the integers, which is incredibly easy.

So what’s all this mean? I’m sure you’ve figured it out by now, but the most likely reason for our ciphertext to be so much smaller than our modulus is because the message was too small and cubing it wasn’t raising it to a high enough power for the result to be larger than the modulus. So let’s just take the cube root of this number and see if we get a meaningful message.

There are various packages we could import that could take an integer cube root for numbers this large, but to avoid that and also show how simple it is, we’ll just implement a simple binary search

CTRL-C, CTRL-V

# pycryptodome

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes

# binary search to find nth root

def get_nth_root(n, num):

lo = 1

hi = num

while lo < hi:

mid = (lo + hi) // 2

test = mid**n

if test < num:

lo = mid + 1

elif test > num:

hi = mid - 1

else:

return mid

return lo

# our puny 1916 bit ciphertext

ct = 3778608670452741690585532070582737668282151949640402971008788675797867361769689843795603772570139166588578774047027062261466175271392436524653959718229204843915061726484932376601163405265201763831847338823471193932707736077364458453053284027613438860180982451957373644892420683829816445662870127785631688212264667656902285465215893696422157358833968897797828703078065238512429996646780856030831270941538206089269140998459840179372535825110571621961016595399813535271853291603009139930478398009395635275428350832860405110482112603276542371203486280518726687143561313790881202021

m = get_nth_root(3, ct)

# make sure we got the actual nth root

assert(m**3 == ct)

print(long_to_bytes(m).decode())

Flagged!

We are in Antarctica, near the independence mountains. HTB{w34k_3xp0n3n7_ffc896}

Recognizing that $e=3$ likely means something, comes from the experience of doing many crypto challenges. The potential weakness of using $e = 3$ is also talked about in many papers and is something you will encounter from experience with RSA. This is why padding schemes are used, messages that aren’t the same bit length as the modulus have padding added to them so that raising them to small powers doesn’t make them vulnerable to this (of course, then there are vulnerabilities that arise from improper padding schemes, Crypto is hard!)

Not knowing any of this already, you could have possibly gotten there just by goolging “common RSA attacks”. The seminal paper on this is this one, most any RSA CTF challenge you come across the method to solve it will be in there. Even if the math is beyond you, it’s worth scanning at least the headings as it will make you aware of what kind of vulnerabilities exist, and from there you can possibly google and either find a script that will solve the problem you’re facing, or a write up that will explain it non academically.

Also, there is always the “common RSA CTF challenges” search. Especially for a CTF aimed towards less experienced people, you probably wouldn’t have to scan through too many write ups to find an identical challenge.

Day Five

Warehouse Maintenance

cliffs: The method of hashing used is vulnerable to a Length Extension attack. Extra commands can be added to the script to read the database and get the flag.

The Challenge

The 10,000ft view of this challenge is that we can interact with a server and if we give it a properly signed message, it will then attempt to execute the message as a series of mysql commands with the mysql instance it is connected to. So our goal then is presumably to exfiltrate the flag from a database contained within.

looking at how messages are signed and verified we see

salt = os.urandom(randint(8,100))

def create_sample_signature():

dt = open('sample','rb').read()

h = hashlib.sha512( salt + dt ).hexdigest()

return dt.hex(), h

def check_signature(dt, h):

dt = bytes.fromhex(dt)

if hashlib.sha512( salt + dt ).hexdigest() == h:

return True

So we have some random number of bytes as a salt, and that is prepended to the message and hashed with sha-512 which is a cryptographic hash function. If you aren’t familiar with hash functions you can basically think of them like a black box, where you give it some input and it outputs seemingly completely random bytes of a certain fixed length (64 bytes in the case of sha-512). If you give it the same input it will always give you the same output. There is no way to tell from the output what the input was, and even just slightly changing the input completely changes the output, so you can’t even tell from outputs if they had similar inputs. Hashing functions are often said to provide a ‘fingerprint’ for data. Those checksums you see for file downloads, that’s what these are. Since the same input always produces the same output, and any change produces a radically different output, you can tell if the file has been tampered with as it will have a different ‘fingerprint’ that what is listed.

Cause I’m long and I’m strong

Given all that, it seems pretty hopeless, how are we supposed create a message that contains mysql instructions and know what hash it will produce since we don’t have the value for the salt the server is using, and if we are off by even a single bit it will fail as the inputs must match exactly. We don’t even know how big the salt value is either! Well luckily for us, we are given this sample script

USE xmas_warehouse;

#Make sure to delete Santa from users. Now Elves are in charge.

and the hash value it produces with the salt prepended to it. That and the simple fact that the salt is prepended to the message and not appended is all we need to forge some signatures using a technique called a length extension attack.

You blockhead!

The way a hash function works, everything isn’t shoved into the black box all at once, it’s input in blocks. Each block is hashed, and the output for all the blocks is then XORed together and this is the ‘fingerprint’ for the input. Also each input block must be exactly the same size (1024 bits in the case of sha-512), if the input isn’t big enough then padding is added.

Let’s look at a smaller simplistic example. Lets say we have a secret ‘SECRET’ and message ‘hello world!’ and a hash algorithm H() that accepts input blocks 32 bytes long. If I feed it the input H(secret+message) since those together are only 18 bytes long, it will need to add 14 bytes of padding to get to its 32 byte input requirement. Say it pads with 0’s so what actually ends up getting hashed when I tell it to do H(secret + message ) is H(‘SECREThello world!00000000000000’). Lets say the output for this block is a8c3ff.

What if now I give it the actual input ‘SECREThello world!00000000000000pwned’? well it will divide that up into 32 byte blocks of ‘SECREThello world!00000000000000’ and since ‘pwned’ isn’t big enough to fill a block it will add enough 0’s to the end until it is (27 of them to be exact) and produce the block ‘pwned000000000000000000000000000’, then it will perform H(‘SECREThello world!00000000000000’) and get a8c3ff and then perform H(‘pwned000000000000000000000000000’) and say the value for that is 56d129, it will then XOR a8c3ff and 56d129 together to get fe12d6.

So H(‘SECREThello world!00000000000000pwned’) is fe12d6

So what if now I didn’t tell you what the value of secret was? I just told you that H(secret + message) outputs ed3398. As long as you know how many bytes long secret is, you know how much padding is being added to H(secret + message), so you could give me the message + padding + ‘pwned’ as your message, and when I prepended the secret to it to hash it, the output from everything up to ‘pwned’ will produce the ed3398 that I told you it would, and you don’t need to know the value of the secret to know that H(‘pwned’) outputs 56d129, because you can put that into the hash function yourself and get the answer. So now you can add anything you want to the end of message + padding and give me a valid signature for the whole thing. You simply get the hash value for what you want to add, and XOR it with the ed3398 that I gave you, and then you give me ‘message + padding + addedstuff’ and when I stick the secret on the front of that and hash it, I’ll get the same value you gave me.

What if we don’t know the length of the secret? Like what if it’s some random length from 8 to 100? We try ‘em all, that’s what we do!

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain

Now I glossed over quite a bit in the preceding example. In reality the padding scheme is different than just adding all zeros (tho only just), there is also an extra little information shoved in regarding the length of the message that I completely ignored, and then one very important fact. Padding is required. If you feed it a message that perfectly fits into X number of blocks, then it creates an extra block of padding. This is done precisely to avoid some length extension attacks, but it also means that we aren’t going to be able to write a simple python script for this. We’d need a working implementation of sha-512 that we could then make encrypt single blocks without adding an extra block of padding, so we could properly fill in the padding and length and not have it add an extra block. These exist but I don’t wanna deal with that (there are also kind of hacky ways around this, but I don’t want to get into that either). So if I’m going to tell you to download something or paste a wall of code, I might as well just tell you to download the tool that will do it all for you. Also, this way I get to be like every pretentious math textbook author and say that the sha-512 pytthon implementation of the length extension attack “is left as an exercise to the reader”.

Can’t stop won’t stop, CTRL-C, CTRL-V

hash extender is that tool (it also contains a very in depth blog post about how length extension attacks work, far better than my muddled example). We connect to the server and get the hash value for the sample signature

─$ nc 138.68.136.191 32483

Welcome to Santa's database maintenance service.

Please make sure to get a signature from mister Frost.

1. Get a sample script

2. Update maintenance script.

> 1

{"script": "55534520786d61735f77617265686f7573653b0a234d616b65207375726520746f2064656c6574652053616e74612066726f6d2075736572732e204e6f7720456c7665732061726520696e206368617267652e", "signature": "4648a504fa6915de4ff4531385028ed71a0f396106c8be9faefc9caa355299b6007c849dbe5dfa72e2e5fd68ac5e02e4d362c10e8224a2265ffa4afe724e0f69"}

We then input that signature and the sample file into hash extender, as well as give it the commands we want to append. We will format those commands in hex tho, as we need to input a new line character and then we don’t have to worry about escaping anything. We are going to tell it to select everything from the materials table. I’ve already done this so I know there is a materials table. I’m just sick of making this write up so am taking the easy way out :) The appropriate first command would be something like SHOW TABLES; Then you’d repeat the process with whatever new commands you wanted to run.

>>> b'\nSELECT * FROM materials;'.hex()

'0a53454c454354202a2046524f4d206d6174657269616c733b'

./hash_extender --file sample -s 4648a504fa6915de4ff4531385028ed71a0f396106c8be9faefc9caa355299b6007c849dbe5dfa72e2e5fd68ac5e02e4d362c10e8224a2265ffa4afe724e0f69 -a 0a53454c454354202a2046524f4d206d6174657269616c733b --append-format hex -f sha512 --secret-min 8 --secret-max 100 >> secrets.txt

We have it output all the valid signatures for secret lengths from 8 to 100, we’ll then write a script to fire them all at the server till we get one that works.

Here is that script. I’m using pwntools to communicate with it

from pwn import remote

import json

# read in and format the file generated by hash_extender

def parse_secrets():

with open('secrets.txt', 'r') as f:

data = f.read().strip().split('\n\n')

secrets = []

for d in data:

entry = d.split('\n')

length = entry[1].split('length: ')[1].strip()

sig = entry[2].split('signature: ')[1].strip()

script = entry[3].split('string: ')[1].strip()

secrets.append((length, sig, script))

return secrets

# connect to server

io = remote('138.68.136.191',32483)

# get to where we can input our data

io.recvuntil(b'> ')

io.sendline(b'2')

io.recvuntil(b'> ')

# get our signatures for the hashes of various lengthed salts

payloads = parse_secrets()

for payload in payloads:

print(f"trying length: {payload[0]}")

script = payload[2]

sig = payload[1]

data = json.dumps({"script": script, "signature": sig})

io.sendline(data.encode())

x = io.recvuntil(b'> ')

io.sendline(b'2')

io.recvuntil(b'> ')

if b'Are you sure mister Frost signed this?\n' not in x:

print(f"response: {x}")

break

Flagged!

trying length: 85

trying length: 86

trying length: 87

response: b"(1, 'wood', 124)(2, 'sugar', 352)(3, 'love', 999)(4, 'glass', 719)(5, 'paint', 78)(6, 'cards', 1205)(7, 'boards', 1853)(8, 'HTB{h45hpump_15_50_c001_h0h0h0}', 1337)"

[*] Closed connection to 138.68.136.191 port 32483

This would be a really tough one to figure out without the knowledge that length extension attacks are a thing. I first learned about it from a currently active HTB challenge (*cough* get those free points *cough*) and I was stumped until I saw a hint in the forum thread for it and finally hit upon a google phrase that got me somewhere. I don’t remember what it was, but suffice it to say, sometimes you can’t know what you don’t know. That’s why participating in the forums and discord and various places is so helpful, no one is on this journey alone and sometimes it takes someone with more knowledge and experience to point you in the right direction.

If you found this walkthrough helpful, please consider adding a respect to my profile, thanks.